What I Did With It Part One: Carry On My Wayward Son

A four-part reflection series told in personal, serialized essays.

There were two defining moments that led me to LGBTQ+ advocacy. One was the death of my great-grandmother—my best friend—affectionately known as Ma. The other was a Tinder date with an older man who’d spent decades in the movement.

I’ve spent my entire adult life advocating for LGBTQ+ rights. I’ll always be proud of the work I’ve done—and the work I’ll continue to do. But there’s more to me than my advocacy. So much more.

I’m a firm believer in context, so let me give you a peek into the road that led me here.

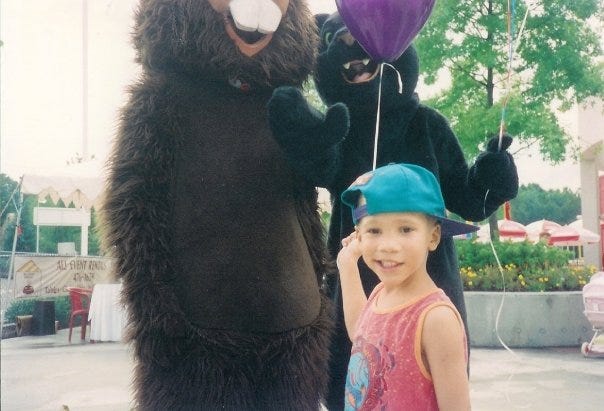

I grew up in Atlanta, Georgia. As best as I can describe it: we always had food on the table and the lights stayed on—but there were no summer vacations, no second homes, and no stashes of money tucked away for emergencies. We had enough, but just enough.

I was straddling two very different cultures. Ma was from Barbados. She spent years cleaning homes, saving every dollar to bring our family to the United States in pursuit of the American Dream. My mom was born in Trinidad & Tobago, and eventually Ma brought everyone to Boston in the '60s. After Ma retired, she and my mom moved to Atlanta to be closer to family. In 1986, my mom met my dad—a sixth-generation Georgian from a deeply Southern family. I was born in 1990, and the rest, as they say, is herstory.

Malik wasn’t the kind of name you’d find on a keychain in a Georgia gift shop. It was intentional—chosen for its Arabic meaning: King or Prince, depending on who you ask.

Some days, I lived the full immigrant experience. We spent weekends at international farmers markets, blasted soca and reggae through the house, and ate roti with curried goat, washing it down with homemade sorrel or ginger beer.

Other days, I was deeply Southern and American—shopping malls, Biggie and Fleetwood Mac on the same mixtape, “Carry On My Wayward Son” by Kansas always in the rotation. Our dinner plates were stacked with fried chicken, collard greens, and mac and cheese—always with a glass of sweet tea or dangerously sugared Kool-Aid close by.

I didn’t always know how to hold both, but eventually, I’d grow to learn that maybe my identity didn’t have to pick a side.

As a kid, I was energetic, creative, and dramatic—but I also felt out of place. My light skin and feminine energy made me an easy target among kids my age. This was Atlanta, and a little Black boy bumping Destiny’s Child and Britney Spears stood out like a sore thumb. Somewhere, there’s footage of me performing a fully choreographed routine—headset and all—to The Boy Is Mine by Brandy & Monica. And I pray regularly that it never sees the light of day.

To assume Ma was just an old lady would be a mistake. Sure, she was the kindest, most giving person I’ve ever known—but she was also quick-witted and unafraid of conflict.

Think: Madea’s personality—minus the violence, and add in regal energy with a Bajan accent.

One day, my mom and I got into an argument. I must’ve still been in the single digits. In the heat of it, my mom called me a ‘son of a bitch’.

Ma stormed in from the next room, looked my mother square in the eye, and said—and I quote, because it was a very formative moment for me—

"Well, we know who the son is. But who’s the bitch?"

I’m pretty sure that was the first time I ever saw someone get read.

Every holiday season, I’d help her in the kitchen as she made her famous Ponche Crème—basically a West Indian version of eggnog. I could barely reach the counter, but I loved being by her side. Looking back, I’m pretty sure she left the rum in when she let me have a taste—but that was our little secret.

In the '90s and early 2000s, there weren’t many safe spaces for kids like me. I spent a lot of time trying to suppress what made me different, looking for moments where I could just be. The churches told me I was a sin. Kids on the playground called me gay before I even knew what the word meant. And some members of my family didn’t hide how they felt about people like me.

I figured out something was different about me as early as eight years old. I felt closer to my male friends—something more than friendship, even if I couldn’t name it. When they ditched our plans to hang out with their girlfriends, I wasn’t just annoyed—I think I was jealous.

It wasn’t until freshman year of high school that I finally admitted it to myself: I was gay.

I’ll never forget seeing my best friend walk down the hallway in a fitted Abercrombie & Fitch henley, the kind that hugged his muscles just right. I looked at him and thought, ‘Wow. He’s hot.’ That brief, electric thought cracked open a door I’d been pretending didn’t exist. And once it opened, there was no closing it.

One of the few places I did feel seen was in the pages of the X-Men comic books. Not because they were superheroes, but because they were born different. They could save the world and still be hated for who they were. Black characters, women, misfits—they were the center of the story. I was obsessed. Comics, movies, television shows, action figures, trading cards, video games—it was my whole world.

My mom swears that one night in ’92 or ’93, she was flipping through channels and landed on X-Men: The Animated Series. I was barely out of diapers, but apparently I refused to let her change the channel. It was love at first mutant.

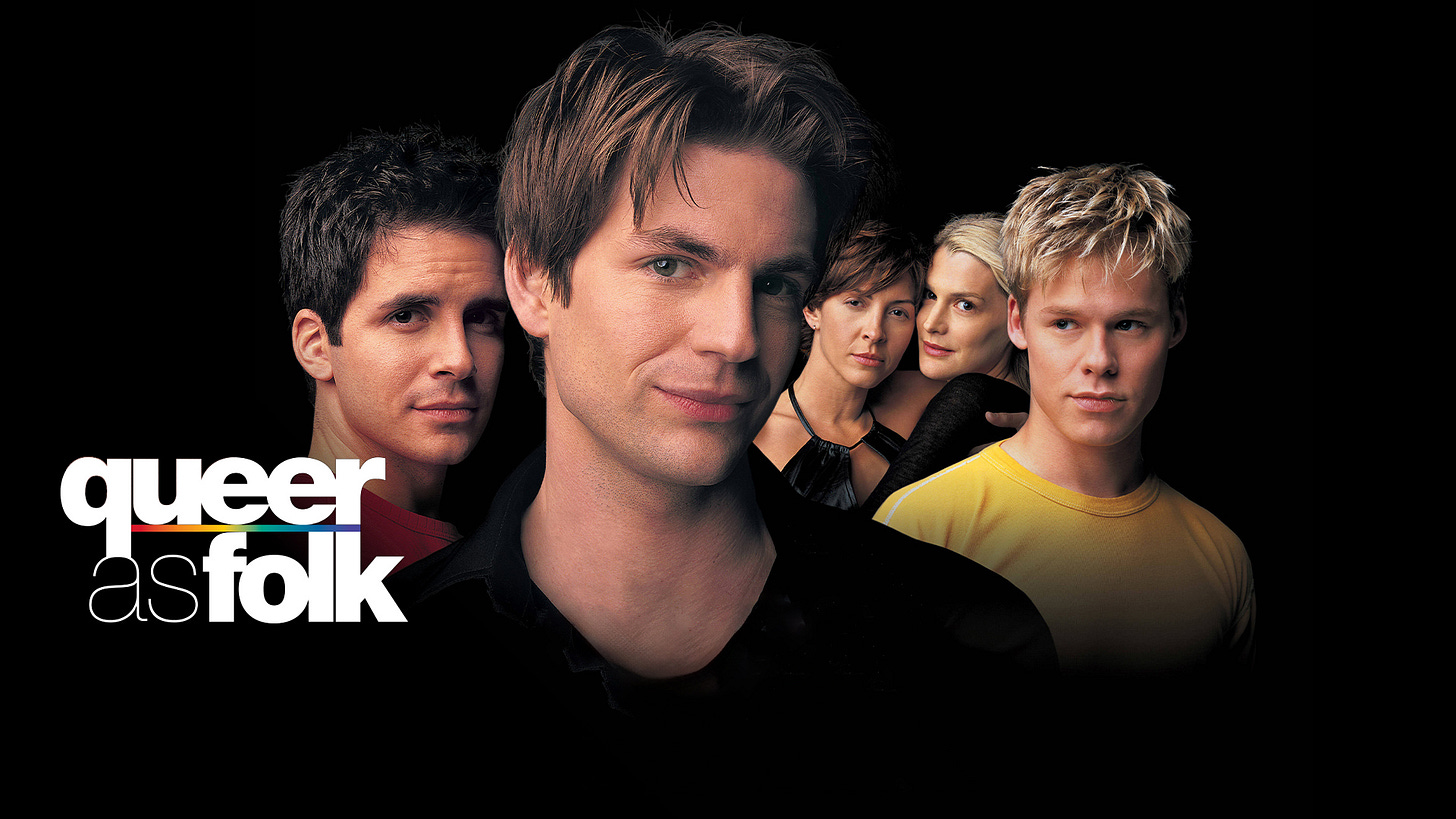

A decade later, while Ma slept in her bedroom, I discovered Queer as Folk on Showtime, and I secretly watched it for seasons. None of the characters looked like me, and I was definitely too young to be a viewer, but it was the first time I saw gay men existing. Boldly. Shamelessly. Freely. It changed everything.

By high school, I’d become a chameleon. I wasn’t popular, but I wasn’t unpopular. I could move between social groups and cliques pretty easily. I remember rehearsing for weeks before I finally told a friend I was gay. He took it well. But the next day I was out sick—and when I came back, everyone already knew.

Someone asked me, “Are you gay?”

It was a question I’d gotten dozens of times over the years, but this time it was different. They had proof. The jig was up. I could shrink again, or I could decide to stand tall. I chose to stand. And for the first time, I didn’t deflect. I said yes.

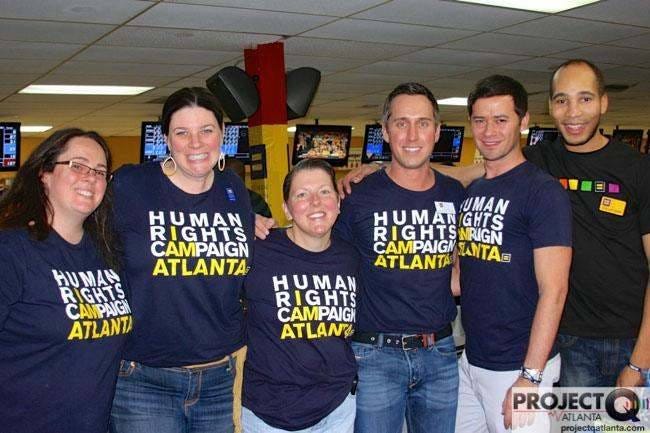

And weirdly… the bullying mostly stopped. Sure, there were kids who tried to use it against me, but most students—and even the teachers—embraced me. I even had a boyfriend or two over the years. I remember watching the Human Rights Campaign and the Trevor Project on the news, fighting against bills like Prop 8 and the Defense Against Marriage Act, and thinking, ‘that’s what advocacy looks like.’

School became my sanctuary—the place I could be out and proud. But back home was another story, one that was much more difficult. I’ll save that for another time.

I remember believing, deep down in my bones, that I’d never be able to be fully myself.

That coming out to my family would cost me their love. That being out at work would cost me my future. That if I was lucky enough to find love, I’d have to hide it. Keep it quiet. Keep it small.

It wasn’t just a fear. It was an absolute. A truth I had accepted without question.

After graduation, I entered my first ‘adult’ relationship. It gave me the courage to finally come out to more of my family—including Ma, who was in her nineties.

I took her to dinner and finally said the words. She’d always been my fiercest protector, but she had made it known over the years that she didn’t support homosexuality. In fact, the views that she shared with me as I was growing up were terrifying. When I told her, I braced myself, preparing to be disowned, but she laughed and said, “I was waiting for you to tell me.”

I was shook. She had unlearned a belief system that was nearly a century old—just to keep loving me. That moment lives in my bones. I’m so grateful she got to know the real me.

A few years later, Ma had a stroke. The doctors told us she would never speak again—and that she had about a week left. But if you knew Ma, you knew some stranger in a lab coat wasn’t going to decide her destiny. Her voice returned—softer, sure—but she wasn’t going out quietly. And she lived exactly one more week.

I spent hours with her in hospice, sometimes overnight, stealing every single moment we could from a world that was trying to take what we’d spent over two decades building.

One night, a small group of family gathered in her room. Ma waved us closer, and we leaned in, thinking she was about to share something profound. Instead, she basically told us to shut the hell up or get out of her room. We were being too loud, and it was her bedtime.

That was Ma. Fierce and hilarious until the very end.

I will always cherish that final week. When she passed, I was 23. I got the call while working on the set of The Vampire Diaries—where I was a stand-in for Kendrick Sampson that season.

Production was incredibly kind to me. Even though it would disrupt the filming schedule, they offered to let me leave. But I couldn’t. I needed to stay. To work. To cling to something normal while everything inside me felt anything but.

Right after she died, I didn’t cry.

I couldn’t understand why.

I had just lost my best friend.

So I threw myself into everything I could control—notifying her loved ones, helping plan the funeral, consoling everyone else.

" Fire and Rain" by James Taylor, "Ronan" by Taylor Swift, and "Brave" by Sara Bareilles became my quiet companions that week, playing on repeat while I kept moving, kept organizing, and kept pretending I was okay.

If I’m being completely honest, the fact that I hadn’t cried started to scare me. It felt like something inside me was broken.

And then, after the funeral, as we stood outside and watched her casket being lowered into the ground, I lost it.

Uncontrollably.

It’s one of the very few times I can remember my father consoling me—especially outside of my childhood.

There was nothing left to plan.

Nothing left to cross off the to-do list.

Nothing left to distract me.

She was just... gone. And the tears flowed, not gently, but all at once. Like a dam giving way.

It was the first time I’d felt true loss, and it was also the first time I felt the weight of legacy. She had sacrificed so much for our future. Now it was my turn to earn it. To make her proud.

A few weeks after the funeral, I swiped right on a man 13 years older than me. To this day, it might still be the most consequential swipe of my life. He was smart, kind, handsome, fun—and had spent over two decades in the fight for LGBTQ+ equality.

Ma came up early in our conversations. I told him I wanted to do something meaningful. I had time. I had energy. I needed purpose.

He made a call.

Next thing I knew, I was volunteering at a fundraiser for the Human Rights Campaign—an organization I’d once watched on the news with wide eyes. That one day changed everything. I found my place. My purpose. My people.

It felt like joining the X-Men—a crew of beautifully different outsiders fighting for a world that didn’t always love them back.

Sure, I wasn’t the leader. I wasn’t Professor X. But I was on the team. And I was damm ready to fight.

More on that next week.